Rethinking Jamestown

America’s first permanent colonists have been considered incompetent. But new evidence suggests that it was a drought—not indolence—that almost did them in

To the english voyagers who waded ashore at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay on a balmy April day in 1607, the lush Virginia landscape must have seemed like a garden paradise after four and a half months at sea. One ebullient adventurer later wrote that he was “almost ravished” by the sight of the freshwater streams and “faire meddowes and goodly tall trees” they encountered when they first landed at Cape Henry. After skirmishing with a band of Natives and planting a cross, the men of the Virginia Company expedition returned to their ships—the Susan Constant , Godspeed and Discovery — and the 104 passengers and crew continued up the Powhatan River (soon to be renamed the James in honor of their King, James I) in search of a more secure site.

They thought they had found it on a marshy peninsula some 50 miles upstream—a spot they believed could be defended against Indians attacking from the mainland and that was far enough from the coast to ensure ample warning of approaching Spanish warships. They set about building a fortress and clearing land for the commercial outpost they had been sent to establish and which they called “James Cittie.” They were eager to get down to the business of extracting gold, timber and other commodities to ship back to London.

But Jamestown proved to be neither paradise nor gold mine. In the heat of that first summer at the mosquito-infested settlement, 46 of the colonists died of fever, starvation or Indian arrows. By year’s end, only 38 remained. Were it not for the timely arrival of British supply ships in January 1608, and again the following October, Jamestown, like Roanoke a few years before, almost certainly would have vanished.

It is little wonder that history has not smiled on the colonists of Jamestown. Though recognized as the first permanent English settlement in North America and the setting for the charming (if apocryphal) tale of Pocahontas and Capt. John Smith, Jamestown has been largely ignored in colonial lore in favor of Massachusetts’ Plymouth Colony. And what has survived is not flattering, especially when compared with the image of industrious and devout Pilgrims seeking religious freedom in a new land. In contrast, the Jamestown settlers are largely remembered as a motley assortment of inept and indolent English gentlemen who came looking for easy money and instead found self-inflicted catastrophe. “Without a trace of foresight or enterprise,” wrote historian W. E. Woodward in his 1936 A New American History , “ . . . they wandered about, looking over the country, and dreaming of gold mines.”

But today the banks of the James River are yielding secrets hidden for nearly 400 years that seem to tell a different story. Archaeologists working at the settlement site have turned up what they consider dramatic evidence that the colonists were not ill-prepared dandies and laggards, and that the disaster-plagued Virginia Colony, perhaps more than Plymouth, was the seedbed of the American nation—a bold experiment in democracy, perseverance and enterprise.

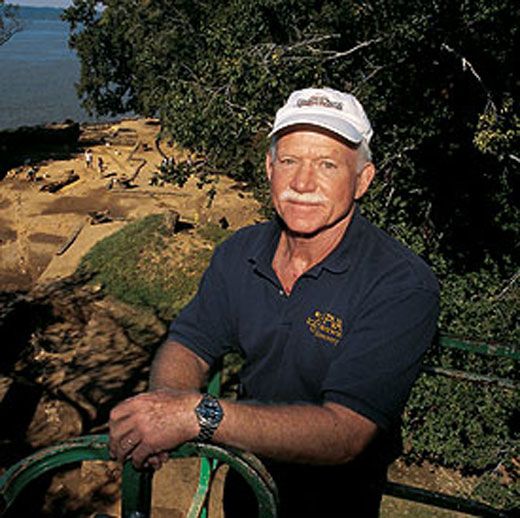

The breakthrough came in 1996, when a team of archaeologists working for the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities ( APVA ) discovered a portion of the decayed ruins of the original 1607 Jamestown fort, a triangular wooden structure many historians were certain had been swallowed by the river long ago. By the end of the 2003 digging season, the archaeologists had located the fort’s entire perimeter on the open western edge of the heavily wooded 1,500-acre island; only one corner of it had been lost to the river. “This was a huge find,” William Kelso, chief archaeologist at the site, said shortly after the discovery. “Now we know where the heart is, the center of the colonial effort, the bull’s-eye. We know exactly where to dig now, and we will focus our time and resources on uncovering and analyzing the interior of the James Fort.”

Since then, Kelso and his team have excavated the ruins of several buildings inside the fort’s perimeter, along with thousands of artifacts and the skeletal remains of some of the first settlers. Only a third of the site has been excavated, and many of the artifacts are still being analyzed. Yet the evidence has already caused historians to reconsider some longheld assumptions about the men and the circumstances surrounding what YaleUniversity history professor emeritus Edmund S. Morgan once called “the Jamestown fiasco .” “Archaeology is giving us a much more concrete picture of what it was like to live there,” says Morgan, whose 1975 history, American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia , argued that Jamestown’s first years were disastrous. “But whether it turns the Virginia Company into a success story is another question.”

The large number of artifacts suggests that, if nothing else, the Virginia Company expedition was much better equipped than previously thought. By the end of the 2003 season, more than half a million items, from fishhooks and weaponry to glassmaking and woodworking equipment, along with the bones of game fish and assorted livestock, had been recovered and cataloged. Many are now on display at the Jamestown Rediscovery project headquarters, a clapboard Colonial-style building a few hundred yards from the fort. “All of this flies in the face of conventional wisdom, which says that the colonists were underfunded and illequipped, that they didn’t have the means to survive, let alone prosper,” says Kelso. “What we have found here suggests that just isn’t the case.”

In a climate-controlled room down the hall from Kelso’s sparsely decorated office, Beverly Straube, the project’s curator, sorts and analyzes the detritus of everyday life and death in the Virginia Colony. Some of the more significant artifacts are nestled in shallow open boxes, labeled and carefully arranged on long tables according to where the items were found. From one box, Straube picks up a broken ceramic piece with drops of shiny white “frosting” attached to its surface. “It’s part of a crucible,” she explains. “And this,” she says, pointing to the white substance, “is molten glass. We know from John Smith’s records that German glassmakers were brought in to manufacture glass to sell back in London. Here we have evidence of the glassmakers at work in the Jamestown fort.” From another box, she takes a broken ceramic piece with a cut-out hole and an ear-like protrusion. She compares it with a sketch of a ceramic oven, about the size of a toaster, used by 16th-century craftsmen to make clay tobacco pipes. Nearby are fragments of a glass alembic (a domed vessel used in distilling) and a ceramic boiling vessel, known as a cucurbit, for refining precious metals. “These artifacts tell us that the colonists weren’t just sitting around,” Straube says. “When they were healthy enough to work, this was an industrious place.”

In another room, Straube opens a drawer and pulls out a pitted piece of iron—round, with a point protruding from its center. It is a buckler, she explains, a shield used in handto- hand combat. It was found in a trench surrounding the fort’s east bulwark. By 1607, she says, bucklers were considered largely obsolete as tools of war in Europe—which would seem to fit the traditional view that the Jamestown expedition was provisioned with castoff weapons and equipment. “But we believe these were deliberately chosen,” Straube says, “because the settlers knew they were more likely to face guerrilla-type combat against Indian axes and arrows than a conventional war against Spanish firearms. So the buckler would have come in handy.”

In the cellar of what had been a mud-walled building that extends outward from the eastern palisade wall, archaeologists have found pottery shards, broken dishes and tobacco pipes, food remains, musket balls, buttons and coins. The cellar had been filled with trash, probably in 1610 during a massive cleanup of the site ordered by the newly appointed governor, Lord de la Warre, who arrived at Jamestown just in time to prevent the starving colonists from abandoning the settlement and returning to England. Establishing the date helps show that the cellar’s contents, which included the glassmaking and distilling equipment on display at the APVA headquarters, dated to the colony’s critical first years. It is from such early artifacts that Kelso and Straube are revising the colony’s history.

Sifting through cellars and trenches in and around the fort, Kelso and his team recently uncovered a surprisingly large quantity of Indian pottery, arrowheads and other items. These suggest that the colonists had extensive dealings with the Natives. In one cellar, an Indian cooking pot containing pieces of turtle shell was found next to a large glass bead that the English used in trade with the Indians. “Here we believe we have evidence of an Indian woman, inside the fort, cooking for an English gentleman,” Straube says. While such arrangements may have been rare, Kelso adds, the find strongly implies that Natives occasionally were present inside the fort for peaceful purposes and may even have cohabited with the Englishmen before English women arrived in significant numbers in 1620.

What is known from Virginia Company papers is that the colonists were instructed to cultivate a close relationship with the Indians. Both documentary and archaeological records confirm that English copper and glass goods were exchanged for Indian corn and other foods, initially at least. But the relationship didn’t last long, and the consequences for both the English and the Indians proved deadly.

As grim as the first year was at Jamestown, the darkest days for the colonists were yet to come. In 1608, the set tlement was resupplied twice with new recruits and fresh provisions from London. But when nearly 400 new immigrants arrived aboard seven English supply ships in August 1609, they found the colonists struggling to survive. In September, the former president of the colony, John Ratcliffe, led a group of 50 men up the PamunkeyRiver to meet with Wahunsunacock—better known as Chief Powhatan, the powerful leader of the Powhatan Indians—to bargain for food. The colonists were ambushed, Ratcliffe was taken prisoner and tortured to death, and only 16 of his men made it back to the fort alive (and empty handed).

That fall and winter in Jamestown would be remembered as “the starving time.” Out of food, the colonists grew sick and weak. Few had the strength to venture from their mudand- timber barracks to hunt, fish or forage for edible plants or potable water. Those who did risked being picked off by Indians waiting outside the fort for nature to take its course. Desperate, the survivors ate their dogs and horses, then rats and other vermin, and eventually the corpses of their comrades. By spring, only 60 colonists were still alive, down from 500 the previous fall.

The starving time is represented by debris found in a barracks cellar—the bones of a horse bearing butchery marks, and the skeletal remains of a black rat, a dog and a cat. To the west of the fort, a potters’ field of hastily dug graves—some as early as 1610—contained 72 settlers, some of the bodies piled haphazardly on top of others in 63 separate burials.

In the conventional view of Jamestown, the horror of the starving time dramatizes the fatal flaws in the planning and conduct of the settlement. Why, after three growing seasons, were the men of Jamestown still unable or unwilling to sustain themselves? History’s judgment, once again, has been to blame “gentlemen” colonists who were more interested in pursuing profits than in tilling the soil. While the Virginia “woods rustled with game and the river flopped with fish,” according to The American Pageant, a 1956 history textbook, the “soft-handed English gentlemen . . . wasted valuable time seeking gold when they should have been hoeing corn.” They were “spurred to their frantic search” by greedy company directors in London who “threatened to abandon the colonists if they did not strike it rich.”

But Kelso and Straube are convinced the fate of the colony was beyond the control of either the settlers or their London backers. According to a landmark 1998 climate study, Jamestown was founded at the height of a previously undocumented drought—the worst seven-year dry spell in nearly 800 years. The conclusion was based on a tree-ring analysis of cypress trees in the region showing that their growth was severely stunted between 1606 and 1612. The study’s authors say a major drought would have dried up fresh-water supplies and devastated corn crops on which both the colonists and the Indians depended. It also would have aggravated relations with the Powhatans, who found themselves competing with the English for a dwindling food supply. In fact, the period coincides perfectly with bloody battles between the Indians and the English. Relations improved when the drought subsided.

The drought theory makes new sense of written comments by Smith and others, often overlooked by historians. In 1608, for example, Smith records an unsuccessful attempt to trade goods for corn with the Indians. “(Their corne being that year bad) they complained extreamly of their owne wants,” Smith wrote. On another occasion, an Indian leader appealed to him “to pray to my God for raine, for their Gods would not send any.” Historians have long assumed that the Powhatans were trying to mislead the colonists in order to conserve their own food supplies. But now, says archaeologist Dennis Blanton, a co-author of the tree-ring study, “for the first time it becomes clear that Indian reports of food shortages were not deceptive strategies but probably true appraisals of the strain placed on them from feeding two populations in the midst of drought.”

Blanton and his colleagues conclude that the Jamestown colonists probably have been unfairly criticized “for poor planning, poor support, and a startling indifference to their own subsistence.” The Jamestown settlers “had the monumental bad luck to arrive in April 1607,” the authors wrote. “Even the best planned and supported colony would have been supremely challenged” under such conditions.

Kelso and his co-workers are hardly the first archaeologists to probe the settlement. In 1893, the APVA acquired 22.5 acres of JamestownIsland, most of which had become farmland. In 1901, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers constructed a sea wall to protect the site from further river erosion; a few graves and the statehouse at the settlement’s western end were excavated at the time as well. In the 1950s, National Park Service archaeologists found footings and foundations of 17th-century structures east of the fort and hundreds of artifacts, though they couldn’t locate the fort itself; since the 1800s it was widely assumed to lie underwater.

Today, the site of the original colonial settlement is largely given over to archaeological research, with few visual links to the past. Kelso and a full-time staff of ten work almost year-round, and they’re assisted by some 20 student workers during the summer. Tourists wander the grassy site snapping pictures of Kelso’s team toiling behind protective fences. Bronze statues of Smith and Pocahontas stand along the James River. There’s a gift shop and a restored 17th-century church. And a $5 million “archaearium”—a 7,500-square-foot educational building that will house many of the colonial artifacts— is to be completed for the 2007 quadricentennial.

The surge in research at the original Jamestown can be traced to 1994, when the APVA , anticipating the colony’s 400th anniversary, launched a ten-year hunt for physical evidence of Jamestown’s origins and hired Kelso, who had excavated 17th-century sites near Williamsburg and was then conducting historical research at Monticello.

Kelso is unmistakably pleased with the revisionist spin his findings have given to the Jamestown saga. Yet rewriting history, he says, was not what he had in mind when he began the work. “I simply wanted to get the rest of the story,” he says. Most of what is known of Jamestown’s grim early years, he notes, comes from the writings of Smith—clearly the most prolific of the colony’s chroniclers—and a handful of his compatriots, along with a few sketchy records from the Virginia Company in London. Such documents, Kelso says, are a “deliberate record” and often are “written with a slant favorable to the writer.” Smith’s journal, for example, frequently depicts many of his fellow colonists as shiftless and inept. But Smith’s journal “is obviously slanted,” says Kelso. “He comes out the star in his own movie.”

An example is the tale of Smith’s rescue by the Indian princess Pocahontas, which Smith first related in his writings in 1624, some 17 years after the incident. Because the story was never mentioned in his earlier writings, some historians now dismiss it as legend—though Pocahontas did exist.

Not that Jamestown’s archaeological evidence is beyond question. Some archaeologists argue that it’s nearly impossible to date Jamestown’s artifacts or differentiate the founding colonists’ debris from what later arrivals left behind. Retired Virginia archaeologist Ivor Noël Hume, the former director of archaeology at nearby Colonial Williamsburg, notes that the fort was occupied until the 1620s and was rebuilt several times. “It’s hard to pin down what the original settlers brought with them and what came later,” he says.

But Kelso and Straube say they can accurately date most of the artifacts and draw reasonable conclusions as to when certain structures were built and abandoned. “If we find a piece of broken pottery in a trash pit, and another piece of the same vessel in a nearby well,” Straube explains, “we know these two structures existed at the same time.” Moreover, she says, the appearance of certain imported items from Portugal, Spain or Germany indicate a period after the Virginia Company lost its charter in 1624 and the colony’s management was turned over to England’s Crown. “It’s really a different Jamestown in the later period,” she says.

Some historians still have their doubts. “What they are finding may require some adjustment to the views of historians relying solely on documents,” Yale’s Morgan concedes. But the reputation of Jamestown as a failure will be a hard one to shake, he adds: “It will take a lot more than a half million artifacts to show that the Virginia Company learned from its mistakes and made a go of it in the colonies.”

Kelso is convinced that much more colonial history lies buried in the island’s soil. During the 2004 digging season, excavators uncovered the footprint of a long and narrow building inside the fort. The presence of unusually fancy glassware and pieces of Chinese porcelain buried inside suggests to Straube that it was a place of high-style dining and entertaining, perhaps the governor’s home, which written records indicate was built in 1611. In the cellar of another structure, a student volunteer uncovered wine bottles, intact but empty, that are believed to date to the late 1600s, when Jamestown was prospering as a tobacco and trade center.

“Were there gentlemen at Jamestown?” says Kelso. “Of course. And some of them were lazy and incompetent. But not all. The proof of the matter is that the settlement survived, and it survived because people persisted and sacrificed.” And what began as an English settlement gradually evolved into something different, something new. “You look up and down the river as the settlement expanded and you find it is not like England. The houses are different—the towns, the agriculture, the commerce. They were really laying the roots of American society.” Despite the agony, the tragedy, and all of the missteps, says Kelso, “this is where modern America began.”